The Salem Athenaeum Exhibition

In October of 2017, Cornelia Jones Gephart presented an essay to the Salem Athenaeum about the man who, heretofore, was unknown to the community.

It was accompanied by a gallery show of 32 of his paintings.

Here is a transcript of that presentation.

Discovering Quinton Oliver Jones (1903-1999)

Quinton Oliver Jones’ history begins with the Jones/Thayer family of Salem, Massachusetts.

Oliver Thayer was born in 1798. As a child, he was stricken with scarlet fever and was sent to sea to recover. Throughout the years, he rose steadily from cabin boy to first mate, then supercargo, and eventually ship’s captain. It was Salem’s Golden Age of Sail and Thayer commanded numerous trading vessels in voyages around the world.

Captain Oliver Thayer 1798-1886

He married in 1824, and in 1840 he retired from sea and bought the fine Federal-style house at 29 Broad Street in Salem. Thayer then enlarged his home to accommodate his growing family of six children and went into business importing lumber from Maine.

The House at 29 Broad Street

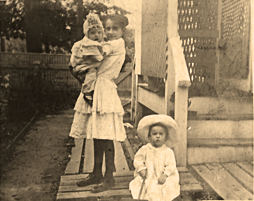

Quinton Oliver Jones is the great-grandson of and namesake of Captain Thayer. Born in 1903, he had two older siblings, Malcolm and Helen. They originally lived with their maternal grandmother and when she died, the family moved to the Broad Street home.

Sister Helen and Quinton, Malcolm sitting

The house was nearly lost in Salem’s Great Fire of 1914. The flames bore down Broad Street fanned by furious gusts of wind. The family fought the blaze by forming a bucket brigade, carrying water up to the attic to douse the roof and ward off burning cinders. The fire was eventually diverted a mere two houses away, and it continued east, eventually reaching the harbor. This devastation loomed large in Quinton’s childhood.

29 Broad Street is on the left

Quinton was nurtured in a warm, supportive and somewhat protective home. However modest the family circumstances, they were passionate about education. There was a tile affixed to the dining room mantle: “Pride costs us more than hunger, thirst or cold.” Quinton absorbed this rather stringent motto and the values of independence, endurance and dedication shaped his life.

Quinton and Malcolm on the right

However, in the summer of 1928, he and Malcolm managed to take a trip to Europe, visiting London, Paris, Venice, and Rome. While in Paris, Quinton would have seen the avant-garde work of French artists such as the “Cubists,” Braque and Picasso. This experience made a lasting impression on him.

In the fall of 1928, Quinton enrolled in the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, to study sculpture, learning stone carving and clay portraiture. In addition, he was given the Bartol Scholarship which was awarded for merit.

An Art Deco relief in sandstone

Over the years, however, he found stone carving very time consuming and poorly compensated. Clay was a different medium, however, in which he found great satisfaction. He learned kiln firing, as well as plaster casting. Back in his home in Salem, he undertook a project of creating clay portraits of children from the Carpenter Street Orphanage (The Seamen’s Widows and Orphans Association). Forty of these busts remain in the 29 Broad Street home to this day.

Three Orphans

In the late 1930s, Quinton turned his attention from sculpture to oil painting and over the remainder of his long life, he created more than 380 canvases. He did some additional sculpture, as well as watercolors and line drawings, and even wrote poems and novel manuscripts.

As a young girl, Quinton’s niece, Cornelia, made a number of visits to her uncle’s home at 29 Broad Street. She remembers saying to her mother, “Wouldn’t you just love to fix up this old house?” Many years later, she inherited the house and she and her husband Dale began a fascinating exploration of all of her late uncle’s works. They were determined to introduce his hitherto obscure creative career to the world.

Quinton Oliver Jones was a very private man. Publicly, he was a quiet, retiring gentleman who kept to himself. Privately, he was alive with ideas and imagination. His mind was in constant dialogue with itself.

QOJ walking Salem’s streets

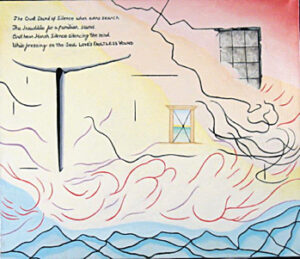

Quinton took solitary walks through the streets of Salem. Many neighbors remember seeing this elderly man, striding along purposefully, head slightly inclined and lost in thought. He could be recognized by the distinctive beret he always wore on his head. Because of deafness in his later years, Quinton was quite isolated on his daily strolls. When Quinton realized he was losing his hearing, his distress at his affliction became the subject of a number of his paintings.

“The Cruel Sound of Silence”

He lived an extremely independent, frugal and simple life. He woke with the sun, cooked his meals on an ancient coal stove, and went to bed at sundown. He was an excellent baker of breads and cookies, drawing on cookbooks from the 19th century.

He did his own home repairs, often with an imaginative use of found materials. He was once given a TV set but ended up using it as a doorstop. His explanation: all the programs he would be interested in came on too late in the evening. Instead, he read voraciously on many topics and in all decades, leaving bookmarks in countless books and magazines to mark his myriad interests.

How did this man, whose life spanned the entire 20th century, come to produce hundreds of works of art commenting on culture, history, politics, and spiritual inspiration while alone in his rambling ancestral home? In short, his art was his life, his passion and the irrepressible creativity that sustained him.

The house and its cultural artifacts, including diaries, photos, magazines, and newspapers—saved by generations—became his inspiration. These, as well as the Episcopal Church and his classical education, provided ample themes for his canvases. He was witness to both astonishing achievements and the devastating wars that ravaged the 20th century. Man’s capacity for menace and evil was often expressed in Quinton’s work.

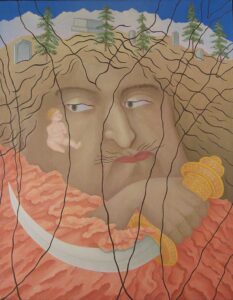

“Herod the Great”

He chose not to communicate about his work. He once laughed and shrugged saying, “No one would be interested in what I do these days.” Other visual themes include allusions to Shakespeare, classical mythology, Christian spirituality, and world history. And he was clearly touched by the innocence and vulnerability of children. He featured them in much of his work; to him they existed in a state of grace.

“Children in Grace”

Quinton was not interested in typical artistic subjects such as still life, portraiture, or landscape for the sake of landscape. In fact, his “landscapes” are quite imaginary. In one of his diary entries, he wrote, “I paint what I think,” and his interpretations became loose narratives, fanciful, and often visionary—what some have called “landscapes of the mind.” His works are fraught with obscure meanings and often the titles are equally enigmatic.

“A Priori”

(Knowledge that comes before experience)

His preferred medium was oil on canvas. His painted surfaces are smooth. His application of color is fluid and seamless, almost an airbrush quality. And his style could change from painting to painting. Isolated as he was, he knew and understood modern trends in art, including Impressionism, Pointillism, Cubism, surrealism and minimalism. And yet, he did not paint for an audience. He deplored the commercialism of the modern-day art world as he saw it.

Here are some examples:

Here Quinton breaks with Western special rules of perspective into planes of color which lead the eye to a central point. And what is it?

“No Thy Past”

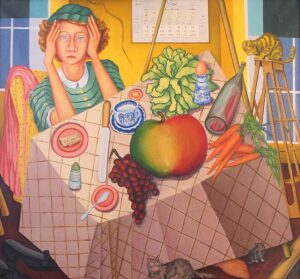

In “Daughter of Eve,” he is entirely comfortable with the Cubist convention of tipping the table top against all reality and enlarging the grotesque dimension, the apple, to make his point. Is she “overwhelmed”?

“Daughter of Eve”

Here an abstract composition, painted with great humor.

“Family Wrangle at Picnic Place –

Rain Shower Approaching”

A few words on color.

Quinton was a magnificent colorist. He was well-versed in color theory, having studied with Arthur Pope at Harvard. Professor Pope published a booklet introducing the most up-to-date scientific explanation of the three properties of color: hue, value and intensity.

While none of Quinton’s paintings were dated on the canvas, there is a “Rosetta Stone” notebook listing all his work with titles, dimensions, and dates.

When comparing his canvases, we can see a gradual shift from the strong saturated colors of his early years—

“Ye Shall Find Rest for Your Souls”

—to soft, atmospheric, opalescent color.

When you let yourself be drawn into the picture you may see images appearing. This is the epitome of Quinton’s skill in handling his pigment.

“An Utterance to the Soul”

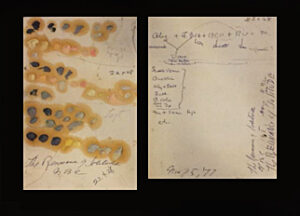

Quinton’s method also included a curious invention: with every completed canvas, he put dabs of the colors he had taken from his palette and put them on a 3 x 5 card. These samples were annotated with the color formula he had mixed, almost like a visual diary. Was he planning to recreate certain effects? We will never know…

Dabs of pigments and the formulas

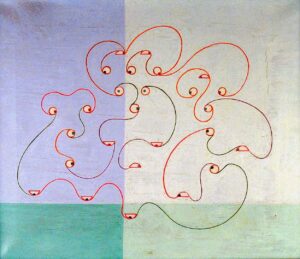

And there is one particularly unique feature in some of his works—his “spirit lines”. With the finest of brush and the steadiest of hand, Quinton superimposed a line drawing that adds a 4th dimension to his painting. These “spirit lines” add a visual activity to the composition, perhaps a psychic depth, but once again, their specific meanings are open to interpretation.

In “ The Apparition,” the “spirit lines” suggest a meaning that we cannot discern, but the human figures all seem to understand them, to fear them, and know that something momentous is about to happen.

“The Apparition”

In “The Botanist,” the “spirit lines” are the subject in themselves as they are imposed on an imaginary landscape.

“The Botanist”

Quinton’s art is not easily or quickly accessible. It often helps to stand before his paintings and let them absorb you, to be drawn in. He is not a “weekend” or occasional artist; most of his canvases contain messages beyond that which meets the eye. Quinton Oliver Jones was an unconventional man, doubtless lonely at times, a deep thinker, an interpreter of history, a visualizer of ideas and emotions and, above all, a believer in the power of art.

Cornelia Jones Gephart is a graduate in Art History from Wellesley College. When she moved with family to Vermont, she began with arts education in the community but then was employed by the United States Park Service at the Saint-Gaudens National Historic Monument as a ranger and interpretive guide.